The Ending's Finality

A while ago I wrote a blog post about the concept of never-ending games and the use of procedural generation. Right now I’m talking about something similar, but from a narrative perspective. There are some MAJOR Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP spoilers in this article. I’ve heard of studies where knowing the ending of something can actually make the story more enjoyable, but if you object to testing that theory on yourself then stop reading and go play that wonderful game! Also, be sure to play it with headphones. I also talk about The Witcher 3 ending but there aren’t really any spoilers.

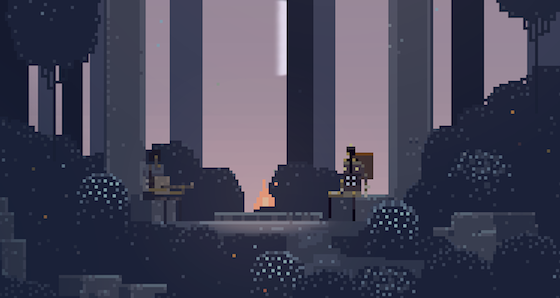

It’s no secret that one of my all time favorite games is Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP on the iPad. The creation of composer Jim Guthrie, Capybara Games, and illustration company Superbrothers. I say “on the iPad” because the game was designed to be a touch based experience; I feel as though just a little of the magic is lost without that aspect or feeling of actually touching the world and other platform specific details that make the piece that much more special.

Part of what keeps this experience so memorable aside from its relative brevity and creative use of the medium is its flowing narrative that brings the world to life and the player into that world. From the start of the game you experience the world through the Scythian, embarking on her “woeful errand”. It becomes clear that her and the player have arrived in a different place that predates their arrival. After the story progresses and a small but memorable cast accompanies throughout, the Scythian’s journey culminates in a climactic battle where she faces the physical form taken by the Gogolothic Mass on the summit of the Mingi Taw. The Scythian defeats the Three Eyed Wolf, but at the cost of her own life. In one of my favorite endings in the history of the medium, the Scythian’s new friends encountered throughout the player’s journey come together and cremate her body before returning to their humble lives on the mountain. The story concludes with a firm resolution to the Scythian’s arc, in some ways it still continues. After the credits roll and the game is put away the world lives on without you, just as it did before you, but forever changed by your brief presence.

Another game I’d like to reference is The Witcher 3. Another near-perfect experience that seized my attention and refused to let go. Intricate storytelling and Tolstoy-esque sideshadowing in a carefully woven yet expansive narrative. After reaching the ending of this story, I was reminded of the power that the destination wields over how the journey can be remembered. After watching how my actions unfolded in the final chapter, I was rewarded with a brief narration telling me how everything worked out for Geralt and the love interest he settled with as well as the larger powers at play. I was a little disappointed to not hear anything about any of the friends that had been with me until the end of the game or what had happened to them. After the credits I was placed back into the world as it was right before the final chapter, or at least, a version of it that lacked all of the main characters. For all intents and purposes, this similar post-game world was my destination. It’s the last place I was when I stopped playing the game and thus the my most recent memory of the story.

While Witcher 3’s technical ending was satisfying, it tacked on an additional piece that became what the player will inevitably feel is the true ending. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild gave players something similar, by taking them to just before the final fight. The difference between these two is that the player is taken to exactly the same place they were just before setting the ending in motion. Everyone is where they were left and all the people met along the journey still live within the world. While this might not fully satisfy the desire to see what happens next, it still accomplishes a firm ending, implies more goes on after the ending, and lets players continue to experience the world. This implementation of post-ending content, leaves the narrative intact by dropping players back into a part of the narrative they’re already familiar with. Instead, Witcher 3 places you into a version of the same setting, where the narrative you experienced feels as though it hasn’t occurred. CD Projekt Red’s approach to this was flawed in that it alters the player’s perspective on the current ‘state’ of the world.

A story achieves a lasting magic by making the world feel as alive as possible. In order to create the illusion of life the world must appear to live, even after the fade to black.